Moral Economy behind the

Dikes

Class Relations along the

Frisian and German North Sea Coast during the Early Modern Age*

Otto S. Knottnerus

From: Regional Implantation of the Labour Movement in Britain and the

Netherlands. Paper presented at the Seventh British-Dutch Conference on Labour History,

Groningen 1990 (= Tijdschrift voor Sociale Geschiedenis 18, Nr. 2, July 1992),

pp. 333-352.

Coastal Society: an Introduction

Rural conservatism has been a

problem to social historians for many years. Ever since Charles Tilly wrote his

Vendée most historians are aware that

unruly peasants normally lack the revolutionary spirit they would have liked

them to possess. Rural conservatism ‑ or rather traditionalism ‑

has been held to be responsible for several interruptions in the process of

modernization. Its advocates could

be blamed for delaying the establishment of the labour movement in many

regions. Adherence to popular traditions may even have tended to serve the

cause of conservatism.

|

Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936) |

Historians and sociologists have

normally taken these rural traditions for granted.[1] Following the trail set

out by Ferdinand Tönnies they saw modern history as the breaking-up of traditional

society under the pressure of intrusive market forces and outright state

intervention. Likewise, labour historians depicted the implantation of the

working-class movement as a breaking away from traditional patterns of

authority and deference. Class-struggle made an end to many centuries of

ignorance and enforced stability.

Here, a different view will be

presented. Traditions and traditionalist ideologies should not be considered as

the preface, but rather as the product of modern society. They represented

purposeful and appropriate reactions to the increasing social mobility, taking

place in a world where chances were still believed to be limited. The heyday of

tradition, namely the 17th and 18th century, coincided

with the birth pains of the modern world economy. Inherent in the delivery were

profound social tensions which often led to violent outbursts. Tradition did

not prevent these outbursts. They rather made them part of a public debate in

which ancient privileges, common laws and eternal standards set the tone.

Indeed, modernization had to make great strides, before people learned that

enduring change was not only possible but also something to be pursued.

This point may need some

clarification. Early modern man could not conceive of change as an ongoing

process of growth and improvement. Rather, he saw one man’s gain as another

man’s loss. The stakes being limited, the losers could only explain their fate

by claiming that the other players got around the rules. Even in the few cases

where there were no loosers (e.g. Holland and Britain), growth was to be

sufficiently exceptional as to allow Providence to be the best explanation for

increasing prosperity. ‘Change’, as Edward Thompson characterized 18th-century

British society, ‘has not yet reached that point at which it is assumed that

the horizons of each successive generation will be different’.[2]

In fact, the idea of progress did

not gain a foothold anywhere before the turn of the 18th century.

Only by then had large-scale industrialization and urbanization started to

create societies in North-Western Europe which were ‘to live by and rely on

sustained and perpetual growth, on an expected and continuous improvement’.[3] Moreover, as the idea

spread from the highest circles downward, it met with considerable resistance.

Potential victims clung to their memory of the past as they tried to combat the

unfortunate consequences of modernization. A whole range of traditions, real or

assumed, was brought into action against what seemed to be the outcome of

forced plans and false projections.

In this respect, some traditions

were more tenacious than others. Their varying capacities to absorbe social

change may have been decisive in keeping a more dynamic world-view at bay. Of

course, in the long run progress could not be halted, nor could its fruits be

denied. By delaying the

advance of liberalism, however, some forms of traditionalism prepared the

ground for conservative world-views which were better able to cope with change.[4] As we will see, the labour

movement’s failure to gain a foothold in certain regions may well be the result

of such early attempts to resist change.

|

Typical Eiderstedt farm or ‘Haubarg’, built after |

We will examine, then, one of the

rural strongholds of early modern capitalism: the North Sea coastal marshes. As

it happens, this region was the model which Tönnies had in mind when he

described a harmonious

rural community (Gemeinschaft), ruled

by tradition. Here actual modernization and presumed traditionalism got wrapped

up in unique way. We will start with some general remarks about early modern

traditionalism. Then, the social, economical and political conditions in the

coastal marshes will be outlined in more detail. This will enable us to

reinterprete many reports about local traditions and social tensions during the

17th, 18th and 19th centuries. It is our claim

that early modernization created a traditionalist ethos, which aimed at

counteracting the unwanted consequences of modernity. The labour movement, in

contrast, tried to break away from traditionalism. It could only do so,

however, when liberalism had loosened the bonds of tradition already. Whereever

liberalism was defeated at an early stage, socialism too, had little chance of

success.

Students often misunderstood these

traditional notions as they copied Tönnies’ opposition of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Of course, the implied

dichotomy between the traditional countryside and the modern urban society has

had its uses. It has been fundamental in many studies concerning rural

modernization.[5] But in their own right,

tradition and modernity can be rather vague and ever misleading concepts.

The Content of Tradition

Early modern society was marked by

the ubiquity of traditions. All over Europe local communities had developed

their own customs and world-views, governing the equitable distribution of

scarce resources among their members, while at the same time excluding others.[6] It might even be argued

that the more commercialized the region was, the more elaborate the pattern of

apparently egalitarian rules, redistributive practices and symbolical

boundaries which one should expect. Rich and poor needed one another. The rich

required helping hands in times of labour scarcity, they wanted fighting fists

to ensure that foreign workers did not hang around after the harvest, and,

moreover, they constantly looking out for popular support in factional

struggles. The poor, on the other hand, expected from their rich fellow

citizens not only charitable gifts in cases of disablement and times of famine,

but a just share in all heavenly blessings. Communication between rich and poor

was highly ritualized, guided by elaborate rules of conduct which were thought

to be very ancient, and indispensable. Thompson has called such traditions ‘the

moral economy of the poor’, pointing out that they might account for the fact

that in 18th-century England the poor were ‘not altogether the

losers’.[7] Reference to invariable

norms and values, publicly shared by all community-members, helped the nascent

working class to mitigate the destructive influence which market forces began

to exert on community life.

In a perceptive criticism of

Thompson, Craig Calhoun has argued that it was the strength of these communal

traditions, rather than class struggle, which largely accounted for what he has

called the ‘reactionary radicalism’ of the early labour movement.[8] There is some thruth in

that, but the fact remains that throughout the centuries agricultural

communities as a rule have absorbed many changes without giving way to less

traditional ways of thinking. Many findings rather suggest that communal

world-views even grew in strength. Their foundations had been laid in the

formation of parishes and commons, by christianisation, by land-reclamation and

dike-building, and not by those ancient Germanic tribal bonds which earlier

generations of historians had so eagerly presupposed. They found their main

extention in an era when the modern state forbade arbitrary use of violence,

and created a common political framework which treated local privileges as part

of a larger juridical and moral order. Their most striking outgrowths occured

at moments when literacy was already universal, and geographical mobility was

becoming more common. Traditions formed the static front of a rapidly changing

social fabric. ‘This, then, is a conservative culture in its forms’, but,

Thompson insisted, ‘the content of

this culture cannot so easily be described as conservative’.[9]

Coastal Society: an Introduction

|

|

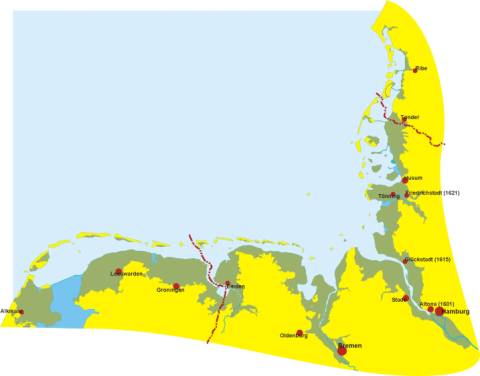

Any student taking a deeper look at

the history of the polderlands along the southern shores of the North Sea will

be struck by the contrasting evidence of tradition and progress. This narrow

belt of fertile marshland, stretching down from the Jutland heaths to the urban

zones at the mouth of the Rhine and Meuse Rivers, extending upstream to the

cities of Hamburg and Bremen, and enclosing the poverty-striken moors and bogs

of the Westfalian and Lower Saxon hinterlands, has been the focus of much

commercial activity for centuries.[10] Here extensive

agricultural exports started as early as the 13th century, and

reached a climax during the Thirty Years War.[11] Danish oxen were

fattened for the Hamburg, Cologne and Amsterdam markets, grains were shipped to

Amsterdam, France and Spain, dairy-products sent up the Elbe, Weser and Ems

Rivers.[12] The large Frisian,

Hanoverian and Holstein horses had a military reputation all over Europe.

Though family-farms were the pattern, the local economy could not dispense with

wage-labour. Unstable weather and critical soil conditions frequently

restricted work to brief periods of the year, thereby causing seasonal labour

shortages which were more serious than elsewhere. Each summer thousands of

small peasants from inland areas marched to the coast where they served in the

corn and hayharvest, earning the money which they took home in order to pay

their rents and feudal dues.[13] More important yet were

the numerous indigenous crofters and villagers. Their help was indispensable,

for they mastered the special techniques of ditching, reaping and diking which

the heavy clay-soils required.[14] But their numbers tended

to shrink, as indigenous population growth came to a standstill during the

general crisis of the 17th century, after the population had reached

the relatively high level of 75 to 125 heads per square mile. The endemic

malaria fevers which probably killed every fourth or fifth resident, delayed

marriages on account of the economic depression, and increasingly restrictive

sexual practices, all contributed to this fall in population.[15] Demands for wage labour,

moreover, tended to swell, as most of the small family-farms gave way to larger

ones because of falling agricultural prices and growing indebtedness due to

wars, floods and cattle plagues.[16]

By the middle of the 18th

century agricultural capitalism was beginning to make a decisive break-through.

By then large-scale arable farms, ranging from 50 to 150 acres, had started to

dominate the coastal scene. Each was employing 3 to 6 working-class families.[17] More hands were required

to manage increasing outputs. Shortage of labour permitted the workers to

negotiate higher wages, better meals and more costly perquisites. Several

generations passed before the resumed population growth had been able to catch

up with growing employment opportunities.[18]

The Napoleontic era brought another

major shift in class relations. Rising grain prices forced the workers to

change their diets from porridge and purchased bread to home-grown potatoes.

This, in turn, eroded many bonds of patronage which linked the workers to the

farmers’ home-economy: increasing dependence on their own crops turned the

scale away from wages and perquisites. Moreover, as grain-exports enriched the

farmers, most workers were not able to keep up with their master’s rising

economic, cultural and educational standards, which drew them away from the

traditional popular culture. ‘The small community had been broken up’, the

Dutch sociologist E.W. Hofstee concluded in a famous study on one of the

coastal regions: ‘At the end of the 18th century farmers and

farm-workers were united. By the end of the 19th century we find two

classes standing entirely apart, differing in manners of living and ways of

thinking, in religious views and moralities, in leasure and enjoyment, in

short, in everything in which two classes can be different’.[19]

For many centuries community-life had

been characterized by the ubiquity of traditions, centering around customary

forms of self-government, and branching out to almost every detail of social

life. The coastal fringe had a long history of political privileges. Regional

identity was ‘closely bound with the idea of liberty’, referring back to some

ancient Frisian or yeomanry freedom which distinguished the coastal

home-counties from the supposedly feudalized hinterlands.[20] During the Middle Ages

about fifty or so more or less independent peasant republics under the rule of

numerous local abbots, chiefs and podesta’s formed a rural counterpart of the

free Hanseatic cities.[21] Many of them were

Frisian. Colonists from Holland settled down in the peat-bogs along the Elbe

and Weser Rivers. The rich fields were veined with waterways that gave free

access to maritime commerce. The autonomous draining organisations provided the

impetus for the development of strong military defence systems. Moreover, the waterlogged

terrain prevented surprises during the rainy season, and made foreign military operations very

difficult at any time. Not until the 15th and 16th

century, and then only at great costs, were the territorial princes able to

incorporate these affluent lands within their own meagre domains. They offered

the ruling landowning and yeomen families extensive privileges in return for

lump sum tax-payments. Up to the 19th century many forms of

estate-like representation, and a massive local autonomy in common law and

civil jurisdiction made the coastal provinces look like an oasis of civil

liberties in a world of authoritarian rule.[22] The inhabitants were, together with the English ‘the most free of any

people in Europe’, the British radical Thomas Hodgskin wrote in 1820 from the

shores of the Elbe: ‘The proprietors ... resemble very much in their hearty

manners English farmers. In Hadeln, however, they are the principal people,

while an English farmer is often of little importance. ... I have seen no place

on the Continent ... that equals the Land Hadeln in the apparent happiness and

prosperity of its people’.[23]

The Dutch provinces of Groningen and

Friesland were somewhat of an exception to this scheme. Here the oligarchy of

newly created landowning aristocracy and urban patricians who seized power

during the 16th-century rebellion, had effectively succeeded in

reducing the peasantry to tenants, and thereby monopolized provincial

government. Also the Count of Oldenburg, as well as some local noblemen down

the Elbe, began restricting the liberties of the peasants. In all cases the

sequestration of extensive ecclesiastical properties during the reformation had

turned the scale against the peasants. But here, too, more localized communal

traditions remained widely in force. The wealthiest of the Groningen farmers

began to make a gradual re-entry in public offices and regional parliaments

from the middle of the 18th century, as leases were declared fixed

and hereditary. Other farmers followed suit. They claimed to enjoy ‘more

liberty than anywhere in the world’, because the landlords could not seize

their riches anymore.[24] The Frisian and

Oldenburg farmers made their re-appearance in public life during the 19th

century.

Coastal privileges, of course, only

applied to the property-owning members of the community. But many notions of

coastal liberty undoubtedly trickled down to other strata. At the bottom of the

social hierarchy these freedoms were probably defended even more rigorously

than at the top. In an East-Frisian joke the boy, whose father is about to

deliver a well-meant blow, cries out: ‘No, father, no, our country is a land of

justice, not force!’[25] Foreign travellers,

indeed, were astonished by the self-assurance of the East-Frisian servants and

farm-workers, and their insistence on inherited rights and privileges. As early

as 1736 the government reckoned with a boycott of farmers who complied to a

newly declared ban on the workers’ habit of smoking in the barns.[26]. A fellow-countryman in

1820 denounced the stubborn resistance against any kind of reform as ‘hardly

believable, and only to be explained by the fact that these people consider any

innovation an interference with their ancient rights and liberties’.[27] In the other districts

the situation was not too dissimilar.

The coastal population felt greatly

superior to the upland dwellers. They were afflicted with a sort of

self-conceit, often resulting in xenophobic reactions against outsiders. In

another joke the boy who wants to see the world is scolded by his father:

‘Shame on you! Here you are in the marshes, the rest of the world is but

heath!’ The migrant workers from the interior were despised throughout. They

were called names, denounced as stinking, stupid and dumb, or even beaten up.

Upland well-to-do freeholders were mocked by the local farm-workers as well as

the farmers, who looked down on them ‘as the Southern hill-billy or redneck is

looked upon by the planters’.[28] Even poor people from

the North-Frisian marshes preferred to beg rather than participate in home

industries as their poor neighbours of the heathlands did. They often refrained

from saving, because they could rely on traditional alms givings and liberal

poor relief to get them through the winter.[29]

Communal traditions and local

patriotism, then, penetrated all the aspects of village life. ‘Folkways, mores

and customary law ... rule the village community and the surrounding district.

They represent the valid common will to which the people there, masters and

servants alike, conform in their daily rounds and common tasks, because, in

their belief, they are bound to do so. For their fathers did so before them,

and everybody does so. And it seems to them the right thing, because it has

always been that way’.[30] So Ferdinand Tönnies

wrote in the 1880s, implicitly referring to his youth in the coastal district

of Eiderstedt.

Obviously, for Tönnies communal

traditions and agricultural capitalism were quite compatible. A recent

biographer bluntly stated that ‘the self-contained autarchic household which Tönnies

posits as the core of Gemeinschaft

still prevailed’.[31] This is to mistake

ideology for fact. Even for Tönnies the reality of community-life was not at

all idyllic.

Contested Communities

|

Farm-workers on strike, Oldambt, Groningen 1929 (from J. Hilgenga, 40 jaren

Nederlandse Landarbeidersbond, 1940) |

Social historians and rural

sociologists have often confused communal ideologies with the communities to

which they referred. Agricultural ‘communities’ were not always as harmonious

and egalitarian as many of Tönnies’ American disciples would have had us

believe.[32] But neither does this

imply that communal strivings and egalitarian views were entirely lacking.

Pronounced social distinctions between farmers and cottars could be perfectly

compatible with an outspoken egalitarian ethos, as the history of coastal

marshes shows. The acknowledged German folklorist Karl S. Kramer, who recently

published about this

region, has seriously underestimated this aspect when he criticized older

views.[33]

Class conflict in the early modern

age had its own logic. Neither communal ideologies, nor social discord, could

be taken at their face value. Both mainly served as a vehicle by which any

group in society could try to find support for its own claims without switching

to open confrontation. Local authorities in the coastal districts frequently

gave in to public demands. Breaking-up the consensus was considered dangerous,

as it opened the way to state interference. Consequently, the threat of

violence proved to be more effective than violence itself.[34] those accused of

offending against communal rules had to climb down if they did not want to

bring the military onto the scene.

This complicated situation provided

the members of the nascent working class with specific opportunities.

Increasingly, the local economy became integrated in international markets and

state policies. The farmers grew richer, but the autonomy on which their wealth

was based also became more fragile. This made them more responsive to popular

claims. At the same time, these claims were stated more vigorously as popular

sentiments became bound up with supraregional ideologies of church, state and -

as far as Germany is concerned - the Empire. Indeed, the defence of local

rights and privileges may have become more influential as the issue lost its

strictly parochial character.

Our sources suggest that coastal

communities were full of unresolved social tensions. Local community leaders,

looking for popular support, could not easily overrule the interests of their

propertyless clientele. Measures against servants and farm-workers, who would

not accept work during the harvest because they considered the wages offered

too low, can be traced back to the beginning of the 17th century.

Apparently, they were not very successful for after the middle of the century,

as inflation ended and daily wages were fixed at a customary level, complaints

about servant pay claims lingered on. This sometimes even lead to the official

settlement of maximum wages and a ban on outward travelling in summer.[35] Material on these

small-scale struggles is scarce because governmental officials as a rule

restricted themselves to the surveillance of public order, but it is clair that

casual labour, e.g. harvesting, ditching and threshing, involved a lot of

bargaining and free competition.

It is obvious, however, that the

workers’ chances of success also depended on the availability of alternative

employment outside the influence of local community leaders. Seasonal migration

to the pastoral areas in the western marshes, employment with the large

peat-digging companies in Groningen, Friesland and Holland, taking service in

the cities, signing on Dutch whaling-boats or coasters, or ‑ not

uncommon during the first years of the 17th century ‑

signing up for in military campaigns could help here. More important still, was

the work on large-scale dike repairs and embankments, organized by

commercially-minded entrepreneurs who offered hundreds of rural workers

temporary jobs. Here as well as in the peat-bogs, strikes were very common.[36] This enabled the workers

to develop an elaborate repertoire of rituals, adopted from military customs

and local diking traditions, by which they could pull together whenever they

felt their earnings were insufficient to support a decent standard of living.

Their experiences as navvies, in turn, had repercussions on labour traditions

at home. The introduction of rape-seed, for instance, induced new harvesting

festivities, which integrated the navvies’ rituals with local customs.

The range of such local traditions

was almost inexhaustible. They applied to work-performance, working-times,

paces and wages. They prescribed the food that could be eaten on week-days and

special treats that should be served at feasts, as well as dictating

table-manners. They specified the supernatural sanctions which would take on

those who worked on holy days. They enshrined the right to visit fairs, to have

special leisure hours, and sometimes, the servants’ privilege to keep open

house for friends and visitors. Even the farmer’s sons and daughters were not

allowed to withdraw from everyday games, competitions and pleasures. Their

involvement did not only legitimize the servants’ behaviour, it also committed

them for years.

Sometimes the farm-workers took part in the litigation about details of work-performance,

as happened in the Land of Kehdingen on the Elbe. On other occasions they were

known to have thrown their meals out of the window when they were served on the

wrong day of the week. Unemployed youngsters and poor people established the

right to go about the village during winter time, singing quasi-religious songs

which paid homage to those who undertook their charitable duties, but also

contained were hidden threats to misers. Martinmas, Christmas and Carnival

givings often sufficed for one or two months. It might have been due to

tradition that agricultural innovations as threshing wagons, Brabant ploughs

and winnowing-machines did not always spread from one district to the other.

These local traditions did not aim

at improving living conditions. They simply tried to maintain the existing

standards. But traditions were malleable. Actual changes could always be

considered as an extension of older traditions. An accusation of breaking an

allegedly ancient custom was, once openly made, perfectly capable of clearing

the ground for new claims. As soon as the accusation had won enough public

support, its denial could be presented as an assault on tradition. Popular

sanctions could inflict serious injury. These could include gossip campaigns,

which could harm a person’s name and solvency, but also legitimize physical

molestation, arson and other forms of maltreatment. A boycott of farmers

unwilling to give way, or infamous accusations directed at workers who accepted

lower standards of pay, were probably the most common forms of open labour

struggle. More, still, were claims and counterclaims contested beforehand, as

farmers had to prove their moral authority by playing their assigned role in

the village ritual. During rape-seed threshing, for instance, the farmer was

violently tossed in a cloth. He could only free himself by offering a banquet

to his workers. Alternatively, the reapers kindly threatened his wife that they

would cut down the winter-stock of kale in the garden if they were not offered a

feast. Here the farmers came to see very clearly what it would mean if they

could not look their poor neighbours, with whom they grew up, in the eyes.

Given these tensions, the older

folklore studies have often arrived at false conclusions about coastal communities.

Like many sociologists, they took existing rituals as the expression of an

harmonious village culture, which was about to disappear. Their conclusions

were misleading, as Karl S. Kramer rightly stated. Traditions around the last

sheaf, for instance, probably had as much to do with recent claims to the

farmer’s riches as with supposedly ancient fertility rites. Going down the road

with lanterns, while indoors fires had just been lighted, must have evoked the

threat of arson. Bonfires in spring may have symbolized the destruction of the

farmer’s winter regime as much as they acted out the burning of King Winter

himself. Community rituals and ideologies, however, were ambiguous throughout,

because they at once presupposed the consensus which they meant to reinstate at

the same time. Even violence itself took on ritual forms, for it aimed at

restoring peace.[37]

![]()

Why did so many scolars mistake this

self-imagined conservatism for the kind of reality which only prevails in

closed communities? Surely Tönnies is not the only one responsible. In fact,

his most famous study Gemeinschaft und

Gesellschaft (1887) is not concerned with peasant communities and

industrial society at all - the way Durkheim deals with the problem - but with

the impact of individualist thinking on an hitherto traditional world.[38] Consequently, his

descriptions of community life must be read as a keen analysis of community thinking too. Moreover, Tönnies did not

want to idealize the vanishing community life. He knew that change was inevitable.

Stemming from an old family of liberal marshland farmers who scorned the

passivity of the upland peasants as well as the traditional go-slow policy of

their own workers, he was not at all sympathetic to an unqualified

traditionalism at all. Folkways and mores, he insisted, were only debated

because they had started to change already.[39]

Nevertheless, Tönnies took an

ambiguous stand toward modern society.[40] Like his 19th-century

liberal predecessors, he felt that progress was the result of purposive human

action. Tenacity of traditions could only lead to indolence and oppression. But

at the same time he was haunted by the idea that the sum of individual actions

did not lead to the intended results. As a sympathizer with the labour

movement, for instance, he deplored the breaking-up of the arrangements which

had protected working people against impoverishment. His analysis, therefore,

concentrated on the rise of the ideology of individualism as much as on the

actual increase of individual opportunities, in order to find the ultimate

cause of the falling apart of community life. This strategy gave him a precise

insight into liberal ideology, aptly. But it did not lead to an adequate

understanding of traditional communities. As Tönnies set out to expose liberal

thought, he took communal world-views for granted. By concentrating on

purposeful action, he neglected the dynamics of those social configurations

where purpose was still disguised as tradition.[41]

Religious Transformations

|

|

This does not mean that we can dispense

with the role of ideologies altogether. This will become obvious, as we finally

shift our attention from traditional culture to religion and politics. It can

hardly be accidental that the most pronounced examples of popular

self-consciousness come from German sources. This may have had something to do

with the fact that the German and Danish Enlightenment created far more

abundant literary sources, but of greater importance were the earlier virulent

campaings of Dutch Calvinist preachers and laymen against popular culture.

Traditions which had survived in Lutheran districts during the 17th

and 18th century, here gradually made way for a new Puritanical

rigidity that had persisted since that time. On the German coast the Lutheran

reformation had carried the day since the middle of the 16th

century. As a state religion, it stood at the base of every local community.

The village church encompassed all community members, the holy mass suggested

their ritual unification with the body of Christ. Lutheranism was the perfect

community religion, for it sharply distinguished the sanctified village

community from mistrusted outsiders. Moreover, local by-laws often completed

this religious communalism, as they made the settlement of any newcomers

conditional on the consent of other residents.

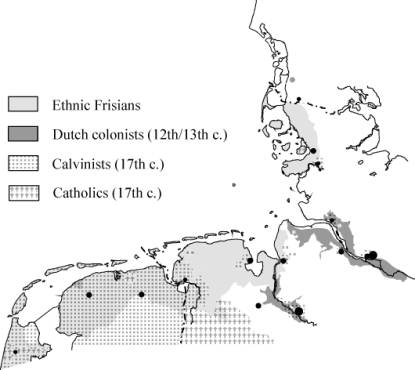

How different, then, were

developments in the Dutch Republic and in the bordering East-Frisian districts?

Here Calvinism, linked with the cause of civil rebellion against the Spanish

crown, had to fight a fierce battle before it could gain recognition as the

official religion.[42] Convinced Calvinists

were a minority group for a long time, having to reckon with the fact that in

Groningen and Friesland alone, at least a third of the country-dwellers were

either Catholics or Mennonites - Menno came from Friesland - , the rest of the

population consisting largely of neutralists and liberals. The sheer fact of

religious diversity made it difficult to sanctify community life.[43]

Calvinist ministers and laymen, therefore, set out to purify their own

religious communities as much as they tried to influence state policies. Taking

the Holy Communion while sitting around a table, they revived the fraternal

rites of medieval guilds, demanding from the participants an unspotted

reputation. At the same time they were ill-disposed to many rituals of public

life, as were the Mennonites before them. Whereever this uncompromising

vanguard of elected Calvinists - it could have served Lenin as an example -

monopolized state-power, it immediately set about reorganizing public life

according to its own standards. Local fairs and festivals were often banned,

dancing made illegal, most forms of conspicuous consumption criticized as

wasteful.

Other religious groups, of course,

tried to obstruct this Puritan offensive. Most formal power remained with

liberal-minded aristocrats and patricians, who did not hide their distaste for

religious orthodoxy. But, when confronted with the threat of religious strife

they too had to indulge the campaign against traditiongewijzigd, and fall back on a strong and neutral

state bureaucracy from where they could better resist Calvinist claims. On the

one hand, therefore, religious pluriformity provided for a secular state, on the other it created the

forces which aimed at reorganizing the society

along Puritan lines.

At the break of the 18th

century in many rural parts of the Dutch Republic and East-Friesland orthodox

Calvinism had incorporated all Protestants except the declining Mennonite

sects. Only in the cities and the urbanized parts of Holland and Friesland on

both sides of the Zuider Zee did a more secular culture continue to flourish. What prevailed was a rich,

but sober style of living and an industrious rural society, which tended to

strip community life more and more down to its essentials, and presented

excessive popular claims as a rebellion against God’s will. But Calvinist

thinking, designated by Tönnies, Weber, Troeltsch and many others as a source

of modern individualist world-views, had its own ambiguities too.[44]

Whereever the state was dominated by

liberal-minded landowning elites, popular claims followed the lines of

Calvinist rigidity. From the pietist movement sprang a new community spirit,

centering around local groups of inspired men and women who insisted that any

chance to be saved depended on the effort to purify one’s life. This religious

revivalism, directed against the liberal clergy, soon became intertwined with

monarchist attempts to curtail the liberal aristocracy and strengthen the

stadholders’ power. The image of God, not as a distant Protector of creation,

but as a being capable of arbitrary interference with human affairs, was

metaphorically mirrored in the image of the righteous but unpredictable ruler.

As one needed no mediators between God and man, so the privileged niches

between subject and state had to be done away with too. God’s chosen community,

be it the village or the congregation, must restore itself by disposing of

false prophets and malicious profiteers.

What concerns us here are not any

essentials of 18th-century Dutch political theory or theology, but

the utopian view of a restored community, a new convenant as theologians might

call it, which allowed the people to participate in community life on a more

equal base than before. Of course, it was very unusual for a common villager to

take part in the Lord’s supper. He often would not have the proper dress to

begin with. The farmers’ position as leaders of the community was uncontested.

They took the lead in religious as well as political affairs. But the

theoretical possibility that a commoner might attend must have opened up quite

new perspectives. Any poor villager could gain respectability by leading a

decent and God-fearing life. His poverty was no shame and his devotion gave him

the right to ask for support from his rich neighbours.

Thus, the traditional village life

faded away and a new and rather untraditional kind of community life

flourished. This lasted as long as the confrontations with the liberal elite

continued. The farmers’ sober appearance and their strict conduct, intended to

challenge the worldly-minded oligarchy, probably served as a model for the

lower classes.[45] Religion disciplined the

poor, but it also gave them new opportunities. In many ways these patriarchally

structured communities resembled Tönnies’ ideal more than anything that went

before. Traditional village culture had faded away in many parts of Friesland,

Groningen and East-Friesland, yet without leading to the class-hatred which raged

later on.

As 19th-century liberals,

including Tönnies, looked backwards, they did not grasp this point. Their

writings on rural welfare and local politics reflected a kind of ignorance and

intolerance towards 18th-century community ideals, which has been

echoed by most historical writing since. In the Netherlands, as well as in the

German states, the farmers gave up many local privileges as soon as they had

acquired the right to participate in state affairs instead. They dissociated

themselves from the impoverished working-class population and got more and more

upset by the fact that many crofters and artisans harked back to the theocratic

spirit of the previous century. Neither religion nor community life meant as

much to them, as they had done to their grandfathers. When the remaining

Calvinist leaders in Friesland, Groningen and the neighbouring German districts

leaders organized their followers, they were met by most farmers with outright

hostility. During the 19th century thousands of ‘small people’ - as

they used to call themselves - left the Dutch Reformed Church for independent

congregations.[46]

There were, however, several

exceptions. In those districts where 18th-century community-life had

been very intense, as in the eastern polderlands of Groningen (Oldambt), or the

Frisian polder-areas (Het Bildt) and peat-districts (De Wouden), the union

between farmers and farm-workers held out somewhat longer. Religious secession

did not take place, and the workers followed their masters halfway to political

and religious liberalism before switching over to more radical views. Another

exception were those villages where communal strife had been totally lacking.

There many farm-workers also followed the farmers towards liberalism.

Again, it is important to stress the

differences between Dutch and German developments. During the 18th

century pietism had gained foothold in many Lutheran districts too, partly

spreading from Denmark southward, partly eastward from the Calvinist districts

in East-Friesland. The links between political and religious grievances were

obvious here too, as conservative protest movements against enlightened church

policies show.[47] German liberalism,

subsequently, took a stand against village traditionalism as much as its Dutch

counterpart did. As early as the end of the 18th century the first

signs of modern individualism began to appear. When, say, some East-Frisian

servants asked for better working conditions, their masters accused them of

breaking an ancient ‘tacit pact’, fixing their rights and duties.[48] The Eiderstedt farmers,

inspired by ‘the system of freedom and equality’, were reported to behave more

and more like aristocrats, while the same time giving way to ‘harshness against

the common man’.[49]

However, where Dutch Calvinist pietism

had substituted a newly developed tradition for traditional village mores,

Lutheran pietism developed largely on the base of traditional community life,

not against it. Northern German liberalism, subsequently, was never met with

any substantive religiously inspired counter-movement. It could do away with

traditionalism rather easily. Either the farm-workers tried to commit the

farmers to traditional values, or they acted in open rebellion, as the 1848

events demonstrate. Gradually, they shifted towards liberalism, ultimately to

socialism.[50] The farmers, on the

other hand, relapsed into conservatism again.

If we consider the subsequent rise

of the labour movement, differences between Dutch and German coastal areas are

even more striking. When German farm-workers started to unite at the turn of

the 19th century, they all found their way into social-democracy,

even in those parts of East-Friesland where Calvinism had dominated for long.

In contrast, the Dutch labour movement only had a chance in those villages

where religious secession had not yet taken place. Often a majority had already

joined the revivalist congregations and showed no interest in trade union

activities whatsoever. These religious organisations, increasingly linked up

with national conservative parties, took an outright stand against socialism

and liberalism.[51]

In certain ways, then, we see in

many parts of the Netherlands a religious type of ‘reactionary radicalism’,

quite comparable to Calhoun’s characterization of the early labour movement in

Britain. As a response, the socialist labour movement in the other districts

often took an outright anti-religious stand, something which was quite

exceptional in Germany.

More interesting, still, is the fact

that anarchism, and subsequently communism, took the lead in some of the 18th-century

strongholds of Dutch Calvinism, such as the eastern parts of Groningen and the

Frisian peat-districts. In neighbouring East-Friesland the Calvinist

farm-workers also took a more radical stand than their colleagues in Lutheran

villages. Dutch anarchism, moreover, had many similarities with 18th-century

pietism. It too depended on charismatic leadership, and displayed a similar

quietism towards organizational matters. When sudden revolutionary change

failed to appear, its supporters also concentrated on self-perfectionment.

Indeed, one is tempted to the conclusion that these radical ideologies owe more

to the egalitarian spirit of Calvinist sects, than to traditional village solidarities

or to modern state-orientated political principles.[52]

The Burdens of Traditionalism

In conclusions: it has long been

recognized that the quasi-harmonious peasant society which was the legacy of 19th-century

sociology, probably never existed. One should not be tempted, however, to drop

the subject altogether. Communal traditions, however difficult to detect, were

always present during the early modern age. Our research suggested that

economic change and social tension in the North Sea coastal marshes led to a

marked increase in traditional notions. We also suggest that some of these

traditions were quite effective in slowing down change and reducing social

tension. Nineteenth-century developments made most of them seen out of date.

Increasing opportunities created a new commitment to change, apparent in

liberal and socialist thinking. Nevertheless, some ideologies, seemingly

hostile to communal traditions,

were perfectly capable of carrying intense community spirit well into the

social complexity of our industrial age. Calvinism was one of these. Whereever

Calvinism had effectively challenged liberalism, labour did not have much

chance.

For centuries many parts of

pre-industrial Europe had been integrated in extensive commercial and cultural

networks. Peasants were transformed into farmers, crofters started working as

regular farm-hands, and their relationship took on more dynamic forms. Yet,

these men and women tended to present themselves as members of closed corporate

communities. We must try to see beyond their self-imagined conservatism. Edward

Thompson has characterized social relations in 18th-century Britain

as ‘class struggle without class’. Indeed: early modern thinking can be

typified as progress without any knowledge of progress, as social change

without social consciousness. Labour historians should take more account of

this.